March 5, 2019

The Leader’s Mandate: Prevent Serious Injuries and Fatalities

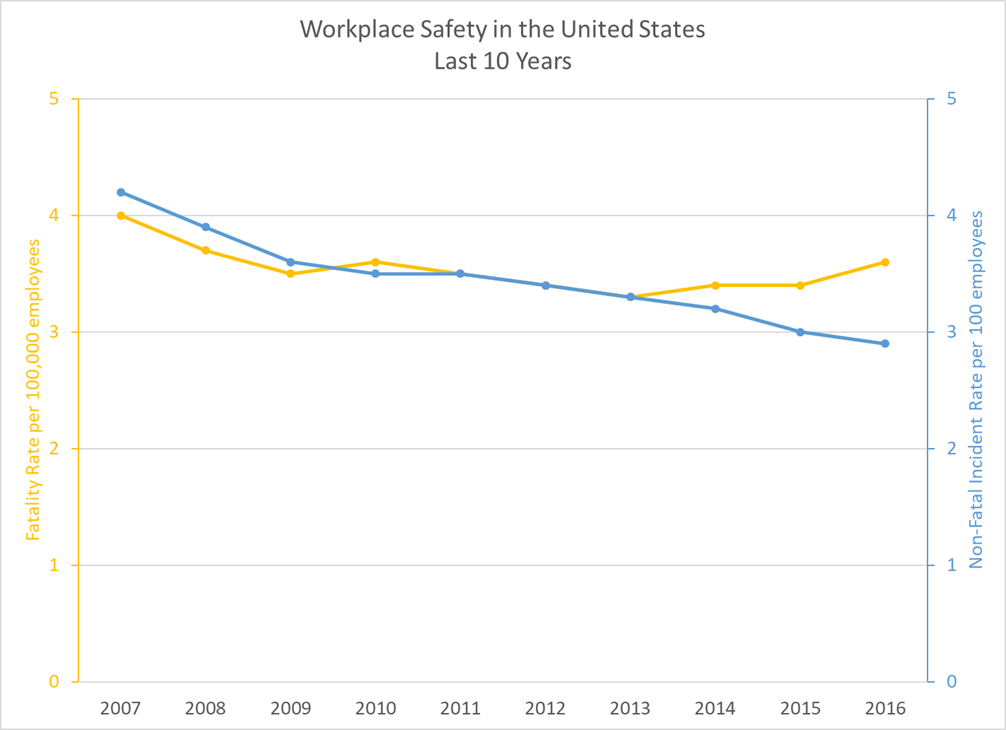

In 2017, the number of fatal workplace injuries in the United States dropped—but only by one percent. According to the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), a total of 5,147 workers suffered a fatal injury in their workplace that year. That was an improvement compared to the previous four years, but in the big picture the workplace fatality count is still significantly higher than the lowest recorded numbers set back in the year 2013. The non-fatal incident rate continues to decline, yet the fatality rate has stagnated. As safety leaders, we still have a lot of work to do to ensure our workers go home safe, each and every day.

A study led by Tom Krause indicates this work must start with a focus on serious injury and fatalities (SIFs). As demonstrated in that 2010 study and described in Tom Krause and Kristen Bell’s book 7 Insights into Safety Leadership, the potential for a SIF event is different than the potential for a minor injury. We’ve spent too long hoping our safety programs focused on the more frequent, less severe incidents will also prevent serious and fatal injuries at the top of the safety triangle. The study showed why preventing life-altering and fatal injuries will require a laser-focus on those precursor activities and circumstances that have the special potential to lead to SIFs.

BLS identifies transportation-related incidents as the highest percentage of workplace safety fatalities—and deaths from a fall from height are at the highest level since reporting started—but each organization must identify and understand their own unique risks and circumstances with SIF potential. These high-risk situations where one or more layers of protection are inadequate, missing, or not consistently used are called SIF precursors. Organizations need to identify situations or activities with SIF potential and determine if there are gaps in operational controls.

Once you have done the work of identifying SIF precursors, it is important to operationalize, sustain, and continuously improve prevention efforts. This is accomplished through the organization’s safety management system, and it aligns with the new ISO 45001 standard, as well as the increased focus on leadership and risks.

We will delve more into the connection with ISO 45001 in upcoming blogs, but it’s worth noting here that the benefits of SIF precursor identification go beyond the areas of risk management and SIF prevention. For example, when a senior leader understands SIF concepts, it changes their safety improvement strategy. Safety goals and resources target the risks and support the programs that can make the biggest difference to worker safety. Employees recognize the investment in practices that safely return them home at the end of the day, and the increase in their engagement that follows improves communication, efficiencies, and eventually the bottom line.

As safety leaders in 2019, our mandate is clear: We need to start by leading with SIF concepts and focus our valuable resources to address SIF precursors. When senior leadership is engaged, and we use our safety management system as a continuous improvement tool for our SIF work, more of our workers will go home safe at the end of the day. We owe them nothing less.

The Leader’s Mandate: Prevent Serious Injuries and Fatalities

March 5, 2019

By Laura FiffickShare this post:

Search for articles