September 26, 2023

How Leadership Decision Making Influences Worker Well-Being

Organizational leaders are increasingly concerned with the well-being of people in their organization, and they should be. Interpersonal conflict, frustration, detachment, absenteeism, and chronic stress are all signs that burnout or turnover are approaching. At a deeper level is the person’s sense of connectedness, inclusion, and efficacy. Deeper still, people want to be part of something worthy; They want to be in touch with the things that make work life meaningful. And importantly, performance excellence requires a foundation of worker well-being.

Although the optimal strategy for genuine, lasting progress in this area is far from clear, leaders need to understand the sources of variation in well-being to develop effective change strategies.

Our purpose in writing this paper is to move towards a common understanding of how worker well-being is created, undermined, and improved. We approach it from the viewpoint of organizational safety, something we have studied extensively1Krause, T.K. and Bell, K. J. (2015). 7 Insights into Safety Leadership. Ojai: The Safety Leadership Institute.

“We know how to make steel.”

We are reminded of a meeting with front-line workers in a steel mill many years ago. They were long-timers who had lived through a work life made up of hard physical labor, heat, noise, dirt and grime, poor lighting and poor ventilation. Our task was to understand the culture they worked in so we could help to craft an improvement strategy.

We asked about their successes and frustrations, how they saw leadership, their experience of the work conditions, and so on. What they said was not unusual: Some supervisors were better than others; Changes in management had caused confusion; Some safety issues were taken seriously and not others. Despite all this, there was the sense that people were deeply engaged. They cared about what was happening.

It was the end of the meeting that stuck with us. One person in the group who hadn’t said much up to that point broke into the discussion. He leaned forward and blurted out: “You don’t get it: We make steel.” It was his way of saying, “Look, consultants, you aren’t asking the right questions. What makes this job great is the sense that we are contributing something of value. We transform carbon and iron into steel.” He was describing what Deming called pride of work, an essential piece of the puzzle that energizes people and creates bonds between them. In this case it overrode everything else.

The bonds that tied these individuals to their company were strong and we could see they were functioning at a very high level. On the other end of the continuum is frustration, avoidance, and detachment leading to burnout. In the middle, as we shall discuss later, are pivotal decisions that leaders make which can move people in either direction.

The Problem is Bigger Than We Think

Burnout in organizations is a far greater problem than leaders often realize, with its prevalence increasing as modern work environments become increasingly demanding and complex.2World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397-422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 Gallup, Inc. (2018). Employee burnout: Causes and cures. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/237059/employee-burnout-part-main-causes.aspx It is not an isolated problem; Increasing burnout in your organization can be a symptom of a broken culture. A broken culture, in turn, will suppress a wide range of essential performance outcomes including safety, quality, and productivity.

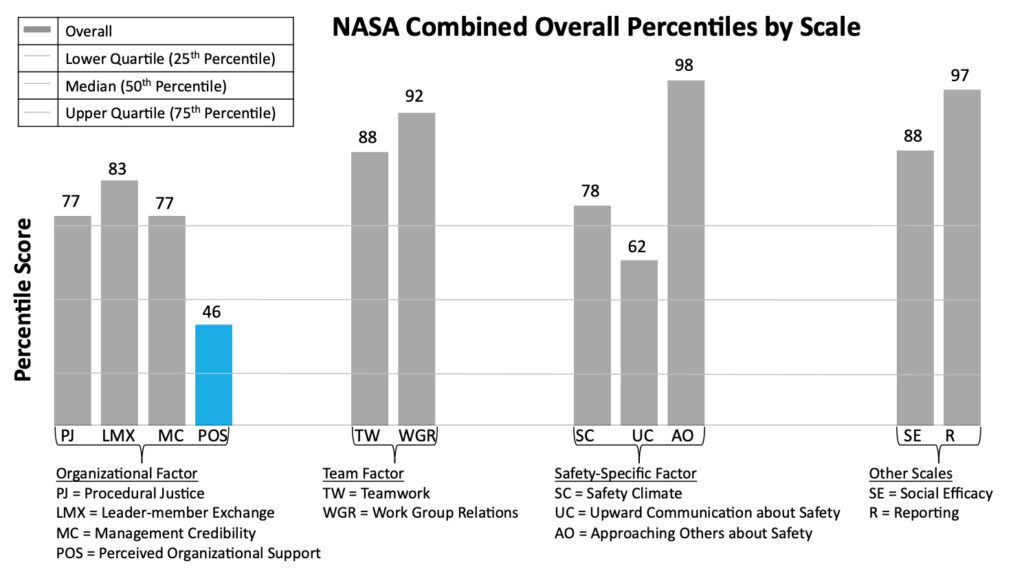

We have seen this time and again in the workplace safety arena, where we are known for our work on safety leadership and culture. NASA, for example, found themselves in this situation after the Space Shuttle Columbia Disaster. The Columbia Accident Investigation Board didn’t just uncover a technical cause (loss of heat shield caused by damage to the foam insulation on the shuttle wing); The Board traced the technical cause and decisions that led to it back to a much bigger problem: a “broken safety culture.” 3Columbia Accident Investigation Board. (2003). Report Volume I: The accident investigation. In G. Hallock (Chair), Columbia Accident Investigation Board (pp. 177-178). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://www.nasa.gov/columbia/home/CAIB_Vol1.html

We had been doing some groundbreaking work on safety culture at the time, and so it was a great honor to be invited to assist NASA’s executive leadership in understanding the problem and helping them get back on track. Though our culture assessment was broad and comprehensive, one variable among several stood out, and we use it here to illustrate. It was the same variable that is central to the issue of burnout: Perceived Organizational Support.4Behavioral Science Technology, Inc. (2004). Assessment and Plan for Organizational Culture Change at NASA. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/57382main_culture_web.pdf We have a different name for it today—Bonding—but it carries all the same power and meaning of Perceived Organizational Support.

Better Understanding of Burnout Leads to Better Solutions

Many organizations attempt to solve burnout by adding assistance programs, new benefits, and richer compensation packages. Sometimes efforts are made to teach leaders to be more empathic. Unfortunately, such well-intended solutions often fall short, and sometimes even make matters worse, at great expense to employers and workers.

Addressing burnout at its core requires a fundamental shift in understanding of what people need to be successful and productive. Leaders who have this understanding can not only protect workers who might otherwise burn out, they can lift every member of their team and help their organizations achieve a new level of performance.

And the good news is that knowledge has developed to make the task easier. Organizational scholars have maintained a body of knowledge that informs the task in a paradigm that includes theory and also specific action and decision making. In this paper, we will explore the central variable we call Bonding. We will show how leadership decision making and behavior influence the Bonding that is the hallmark of a high-functioning organizational culture.

Bonding is a central attribute which, if missing from your culture, exacerbates the progression of factors leading to burnout. If present in your culture, it has the ability to unleash discretionary energy, motivate people, and create the conditions for very high organizational functioning, which predicts performance excellence.5Eisenberger & Stinglhamber (2011). Perceived Organizational Support: Fostering Enthusiastic and Productive Workers. Washington, D.C.. American Psychological Association.

Bonding

Simply stated, Bonding refers to workers’ connection to their organization that arises when they can see how much their organization values and supports them. It is hard to over-state the importance of this central factor of organizational life, which channels through leadership behavior and decision making. When people feel connected, they become energized and motivated, and they reciprocate by contributing above and beyond the requirements of their jobs. This shows in hard data on productivity, safety, and quality. Crucially, people who have bonded in these ways are better able to cope with everyday stresses of the job. It makes the difference between being stuck with a frustrating problem and finding ways to solve problems that make the group better. Weak bonding leads to the progression of factors that lead to burnout, including absenteeism, decreased productivity, burnout, and increased turnover.6Eisenberger & Stinglhamber (2011).

Triple Bonding

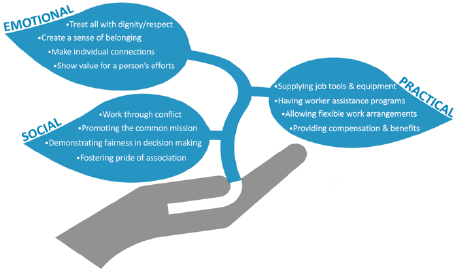

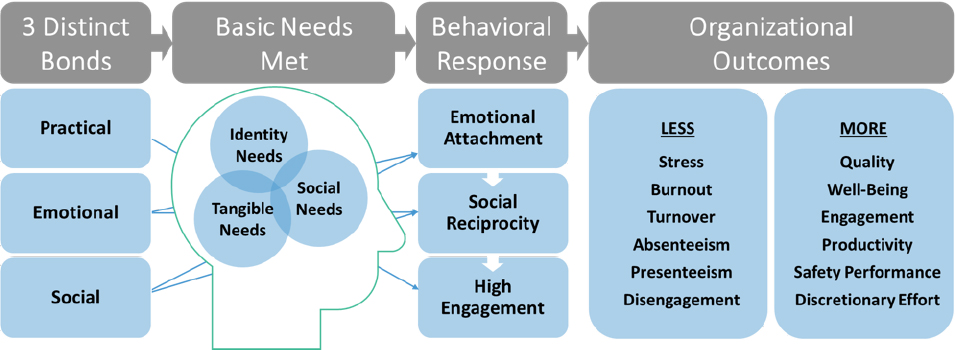

Research has identified three important ways people form bonds with their organization: There is a social bond, an emotional bond, and a practical bond. When people are connected to their organization in all three ways, the result is stronger and more stable relationships leading to higher engagement and better functioning.

And the great news is leaders can cultivate all three through their decisions and behavior.

Leaders foster practical bonds through decisions related to compensation, benefits, and providing resources to do the job. Leaders encourage emotional bonds in the ways that they interact: being inclusive, treating every person with dignity and respect, showing value and appreciation for the work people do. Leaders facilitate social bonds by creating a sense of meaning and purpose in the work being done as well as fairness in decision making. Leaders who cultivate Triple Bonding in their people are more likely to have high functioning and stable teams.

Research in the last 10 years has helped to explain how–and why–Bonding has such a profound and enduring effect on organizational outcomes.7Riggle, R. J., Edmondson, D. R., & Hansen, J. D. (2009). Advancing organizational support theory into the twenty-first century world of work. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(2), 193-203. Bonding is a mechanism through which individual needs can be met, and when these psychological needs are met, people respond with all kinds of high-functioning behavior. They reciprocate with discretionary effort (reciprocating behavior), they exhibit loyalty to the company (attachment behavior), and they increase engagement in their work. The organization sees positive outcomes too: increased production volume, sales, quality, safety, innovation, profitability, etc.

Organizations are not the only beneficiaries of Bonding. Individuals are getting their psychological needs met, and this is creating a sense of well-being that protects them from stress, frustration, and detachment leading to burnout.

Pivotal Decisions

We’ve studied leadership decision making extensively, across organizations, most often in relation to poor safety outcomes.9Krause, T. R. and Bell, K. J. (2023). Organizational Decision Making for Safety: Confidential Research Report. Ojai: Krause Bell Group. Our experience has been that a set of identifiable decisions create the circumstances leading up to a catastrophic event such as burnout, or a fatality, or explosion. Pivotal Decisions are even more important: In the context of this paper, pivotal decisions are those that either push people towards burnout and cause organizational dysfunction; or enhance well-being and organizational functioning.

One consistent finding from our work is that decisions often break down at the level of awareness and are influenced by cognitive biases. Each organization needs to understand the relationship between decision making and detachment leading to burnout. Here are some questions to answer:

- What types of decisions are related to a culture high in detachment leading to burnout?

- What level of leadership is most frequently making decisions of this kind?

- What kinds of decision biases compromise the quality of decision making?

These questions can be answered for an organization by decision analysis methods. This can be approached on two levels, both important: Individual cases and themes across cases.

An Individual Case

John was a good supervisor for several years after he was promoted from his job as a maintenance mechanic. Then his performance began to slip. He was absent more days than usual, his reports were late, and people on his team started asking to be re-assigned. His team began falling behind on work orders and they received low scores on a safety audit. Operators started to avoid John’s team when they needed maintenance support.

When John’s supervisor approached him about his performance, John said things weren’t going so well at home. A few months later, received a poor performance review. Shortly after that, he resigned and went to work for another company. How did this happen?

Interviewing people familiar with the situation revealed a deeper story. The site’s maintenance management system had been replaced by a new corporate-wide system. The change created new reports and procedures that John didn’t understand fully or support. It looked to him like more paperwork, for no good reason, and without benefit to him or his ability to do his job well. When he complained about the system, his supervisor took it as a sign of an attitude problem and ignored the situation. Soon after, John received a poor performance evaluation. John thought it was unfair and inaccurate, but he didn’t see a way to deal with it. He was feeling stressed, and his work suffered as a result.

The following decisions were identified as important in creating the context leading up to John’s resignation. Notice how they either enhance, or interfere with, the different types of bonds people make:

Practical Bonds

- A decision to implement a new maintenance management system made it more difficult for John to work efficiently and effectively.

- A decision to give John a poor evaluation affected John’s perception of the likelihood of rewards in the future.

- A decision to pay median wages affected John’s perception of his earning potential with other companies.

Emotional Bonds

- A decision to allow John to work in continuous frustration without helping him work through the problems caused him to avoid work and he eventually disconnected altogether.

- A missed opportunity to explain reasons behind decisions impacted John’s motivation to learn.

Social Bonds

- Decisions to avoid John and his team made John feel alienated and fed a downward spiral.

- A missed opportunity to learn when the relationship between maintenance and operations began to break down, allowing that alienation to continue.

Themes Across Cases

Pulling together learnings across several cases like this can help to isolate pivotal decisions. Continuing the above example, we might discover two or three themes that cut across cases, such as:

- Management of Change: When changes are made that affect how work gets done, what is the process for identifying and managing the multitude of impacts?

- Leadership Interactions: When people underperform and/or conflicts between teams are observed, do leaders engage in careful listening to understand the problems that need to be solved?

- Talent Strategy: When implementing a compensation strategy in which people can earn similar wages elsewhere, what other mechanisms are in place to help people form strong bonds to the company?

Burnout as well as the progression of problems that precede it, are not just personal problems, but also indicate wider organizational issues that can hold your company back. Fortunately, the same cultural attribute that protects your organization from burnout is also responsible for the conditions in which people, and the organization thrive. Understanding the crucial role of Triple Bonding, combined with a deeper understanding of how it gets created, can help senior leaders design effective organizational improvement strategies.

References

How Leadership Decision Making Influences Worker Well-Being

September 26, 2023

By Tom Krause & Kristen BellShare this post:

Search for articles