April 5, 2023

Organizational Decision Making for Safety: Part 1

Organizational Decision Making for Safety: Part 1

New Research and Implications for SIF Prevention

Introduction

The notion that leadership matters to organizational safety is intuitive for most people. Over the years, we have accumulated a thorough understanding of certain aspects of safety leadership, what excellence looks like, and how that leads to safety improvement. Countless books have been written, leadership assessments have been developed, and organizations have entire programs dedicated to developing the safety leadership skills of their employees. Despite this progress, decision making for safety is an aspect of leadership that has not received enough attention. Until recently, we hadn’t recognized the extent to which two things matter:

- People at every level are making crucial decisions that impact safety.

- Leadership decision making is pivotal to the understanding and prevention of serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs).

In this two-part series, we examine the evidence for these statements and their implications for policy, strategy and the role of senior leaders in SIF prevention. In Part I, we explore significant, and previously unrecognized, findings that can impact safety. Part II takes a closer look at key highlights from the study and the implications for business performance.

New Research on Decision Making in Safety

Extensive research in psychology over the past few decades has deepened our understanding of how our brains work and how people make decisions. We discovered that humans are not perfectly rational decision-makers; we don’t always make decisions that serve our best interests. Two psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, showed that human decision making is subject to error and thanks to them, we are now able to anticipate and even quantify natural failures in our thought processes[i]. Despite successful applications of their work to economics, law, marketing, and public policy, we are only now starting to understand how this decision-making research applies to safety.

In 2015, Krause Bell Group sponsored collaborative research to explore the very broad question, “What is the role of decision-making in serious injury and fatality prevention? Our Safe Decision Making® (SDM) Innovation Group enlisted thought leaders from ORCHSE and six major corporations representing different industries. We pooled data, experience, and expertise in attempt to answer questions like,

- Who makes safety related decisions?

- Which decisions are most important?

- Which cognitive biases affect which kinds of decisions?

- Can we improve safety by improving decision making skills and knowledge?

Participating companies contributed information from 60 SIF events. From these, we carefully extracted and analyzed over 600 decisions, and were rewarded with powerful insights.

Key Finding: Whose Decisions Matter?

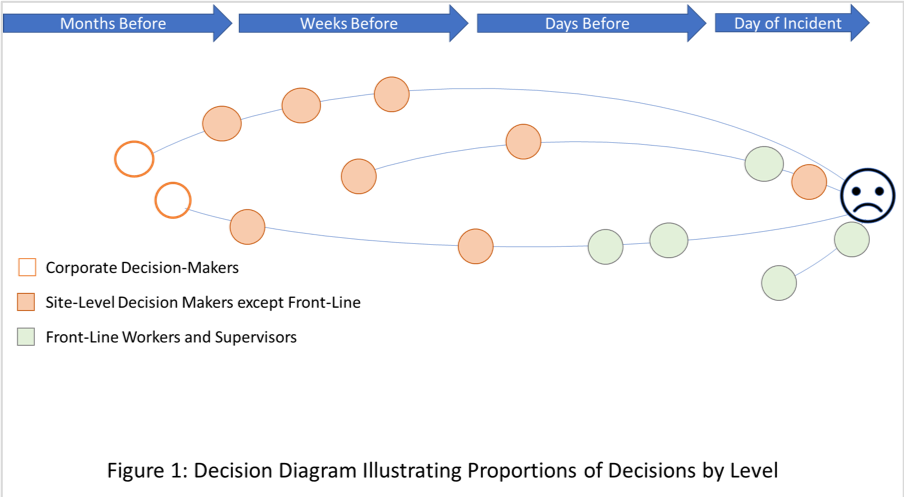

It seems intuitive that everyone’s decisions matter, but one of the most pronounced findings of the study was that decisions made above the front line play a bigger role than we expected. Of the over 600 decisions found to have influenced the 60 SIF events, two-thirds were made by individuals in management positions. Additionally, the clear majority of those were made by site level managers. Front-line workers made fewer than 20% of the decisions leading up to a serious or fatal injury.

The extent to which site-level leaders’ decisions impact safety is not fully appreciated in today’s organizations. Managers know that they need to make sound decisions because ultimately, “a company’s value is no more (and no less) than the sum of the decisions it makes and executes.”[ii] Yet, this understanding has not carried over into the safety arena to the extent it should.

The Shortest Distance to Zero

Until leaders at every level understand their connections to safety improvement, we will miss opportunities to have a long-lasting, far-reaching, game-changing impact.

It is critical that these findings not be misconstrued as blaming the manager. This makes no more sense than blaming the worker. What this suggests instead is that leaders are positioned to have a greater influence over safety than previously recognized, and by creating the right context for their decisions, equipping them with appropriate and timely information, and strengthening their Safe Decision Making® skills, they could provide the greatest opportunity in safety improvement.

The shortest distance to a zero-injury rate may be through a vertical slice of decisions made at the top, middle, and bottom of the organization. As the data are telling us today, decisions at each level are connected to one another and interact to create a Safe Decision Network.

In Part 2 of this series, we dig deeper into the types of decisions that played a role in the 60 SIF events. We explore how those decisions break down and whether it is possible to improve SIF-related decision making. In the process, we suggest practical steps towards even more effective safety leadership.

References

[i] Kahneman, D., Slovic, P., & Tversky, A. (Eds.). (1982). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809477

[ii] Blenko, M. W., Mankins, M., & Rogers, P. (2010, June). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2010/06/the-decision-driven-organization.

Acknowledgements

Christina Thielst contributed to the writing and editing of this article.

Organizational Decision Making for Safety: Part 1

April 5, 2023

By Kristen Bell & Tom KrauseShare this post:

Search for articles