May 14, 2024

How Safety Improvement Works — Part 3

Safety-Related Decision Making and Implications for Serious Injury and Fatality Prevention

In the first and second article of this series, we explained the importance of safety leadership to initiate and drive safety improvement. We showed how leaders can impact safety performance through continuous improvement processes like meaningful safety conversations and strategic risk reduction. This approach not only prevents fatalities but also creates the kind of culture that transforms the business.

Recent studies have made something new and exciting clear: The central theme, the through-line most useful to SIF prevention, is all about decision making for safety. Yes, reducing exposure to risk and improving the culture are crucially important. But how do leaders at different organizational levels influence those things most effectively?

Consider the decisions that have been made in your organization. In retrospect, after a serious injury or fatality (SIF) event, you can see how various levels of decision making have set the stage. Decisions related to investment, organizational structure, operational processes, and hiring can easily be traced to it. In our old way of thinking, none of these were safety decisions because they weren’t the responsibility of safety professionals. Today, we recognize that all of these are safety decisions because they impact exposure to risk and organizational culture.

Studies by the Krause Bell team offer a deep dive into decision making as a key lever for safety improvement. In the next section, we review our 2015 study of over 600 decisions related to serious injuries and fatalities. From this study, a new and better strategy for transforming organizations has emerged.

Which decisions matter most to SIF prevention and on what organizational level are they occurring?

Our 2015 study began with identifying critical decisions. People make decisions all the time, but some impact risk and culture more than others. Decisions at the front line normally impact a local situation while managerial and executive decisions often have long term and broader impacts. In our study, we came across highly impactful decisions related to business strategy, budgeting, organizational structure, talent, and many more.

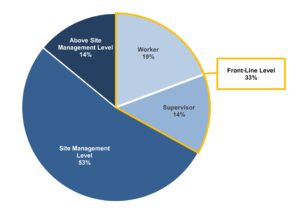

When people hear our Safe Decision Making® phrase, many people assume we’re focused on front-line worker decisions. Figure 1 shows that in our 2015 study, just 33% of the decisions were made at the front line. 67% were made at the site leadership level and above.¹ Because these decisions are not isolated – they connect to each other – your opportunity as a leader isn’t to change the front-line worker decisions directly. The real opportunity is to discover how your own decisions are affecting the organization around you. It’s the organization influencing worker decisions, and you affect the organization.

Figure 1: Managerial Decisions have Leverage

The Blind Spot: We don´t know what we don´t know!

Once we identified decisions that mattered to the SIF events, the question became, where are these decisions breaking down? Having this information allows one to design high-leverage improvement mechanisms for people and teams.

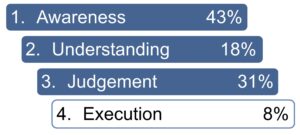

It is tempting to equate bad decisions with poor judgement, but that may not be the case at all. The study showed that decisions break down at every step of the decision making process (Figure 2). In that group of decisions, the most common breakdown occurred at Awareness, which means leaders did not recognize they were making a safety-critical decision.¹ Although recent studies uncovered new kinds of decisions that broke down elsewhere, it is still the case that the first skill individuals and teams need is awareness that they are facing a safety-critical decision.

Figure 2: Decisions Break Down at Different Steps of the Process

Knowledge of precursors to SIFs can help increase awareness of safety critical decisions, particularly at the front line. For more on this, click here.

Cognitive Bias: How our brain tricks us into flawed decisions.

The third question we explored was: how can cognitive bias influence safety-critical decisions?

The concept of cognitive bias was first discovered by two psychologists, Daniel Khaneman and Amos Tversky. In a research collaboration that lasted over a decade and led to Khaneman receiving the Nobel Prize in Economics, the pair set out to uncover and explain large, persistent, and serious errors in judgement that undermine every human being’s ability to make rational choices.

We recognized opportunities for cognitive bias in almost every decision in the study. At the management level, the top three biases were Availability bias, Overconfidence in Others, and Categorization Bias. At the front-line level, the top three biases were Status Quo Bias, Normalization of Deviance, and Overconfidence in Self.

Top 3 Biases Recognized in Management Level Decisions

- Availability Bias — e.g., assigning the first person you find to a task without taking the time to review other options

- Overconfidence in Others — e.g., asking a regional safety manager who oversees 44 locations to personally monitor safety on a high-risk job site

- Categorization Bias — e.g., treating all crane installation projects as “the same,” thus granting exemptions from important risk assessment and verification steps

Top 3 Biases Recognized in Front-Line Level Decisions

- Overconfidence in Self — e.g., attempting to clear a jam without de-energizing the equipment first

- Normalization of Deviance — e.g., violating a safety standard to enter a grain silo becomes so common that people no longer see the risk

- Status Quo Bias — e.g., using the same pre-task plan day after day without considering what is different each day

Improving Decision Making: A New and Better Strategy for Transforming Organizations

These findings from 2015 inspired a body of work to develop and test strategies for transforming organizations through improved decision making. We are using our growing database with over 4000 decisions to continue extracting insights that will allow leaders to fight cognitive bias and strengthen decisions in their organizations.

Every company is different. However, there are some common themes across improvement strategies that are working the best. These include:

- Senior executives need to be aware of the organizational decisions related to each SIF event, and each SIF precursor.

- Mechanisms must be in place at the site level to identify and address SIF precursors.

- Often addressing site level SIF precursors requires the perspective and decision making power of the senior leader.

The next article in our series will touch on how best to sustain safety improvement. Just one spoiler: it comes back to leadership decision making.

¹Krause, T. & Bell, K. (2015). Findings from the 2015 Safe Decision Making® Study (Updated 11/4/19 – 612 Decisions) [Data file and code book]. United States: Krause Bell Group.

Search for articles

Share this post: